A Relaxed Mind is a Productive and Creative Mind

Our Brain on Stress

When we’re under stress, the brain secretes hormones like cortisol and adrenaline that in the best scenario mobilize us to handle a short-term emergency, but in the worst scenario create an ongoing hazard for performance. In that case, attention narrows to focus on the cause of the stress, not the task at hand. Our memory reshuffles to promote thoughts most relevant to what is stressing us, and we fall back on negative learned habits. The brain’s executive centers—our neural circuitry for paying attention, comprehending, and learning—are hijacked by our networks for handling stress.

“A relaxed mind is a creative mind and a creative mind is a relaxed mind and only a relaxed mind can become a one-pointed mind, and a one-pointed mind is the most wonderful mind; it is the most powerful, it can do anything.” Yogi Bhajan

Emotional Contagion

Emotional contagion is the phenomenon in which a person "catches" the emotions of those around her or the emotional ambience of her environment. As is often observed, people find laughing and yawning contagious. The same effect also occurs with emotions. We can become depressed when surrounded by sad people, or find our feelings chiming with a happy ambience. Sometimes one child's crying elicits tears in another, though the second is not sure why the first is moved. After outlining more common kinds of emotional responses as well as the human-to-human case of emotional contagion, I describe contagion-like responses to the weather, to colors, and to music. Contagion represents just one of several ways music might elicit emotion in listeners (see Juslin and Västfjäll 2008), but such responses are common and intriguing, and there is growing interest in the mechanisms underlying emotional contagion. Emotional responses Usually our emotions are targeted at an object. I am afraid of the angry man who confronts me. The object often is apart from us, in the world, but it may be internal. I am afraid that I will give way to temptation. The emotion's object is typically believed by the emoter to possess qualities relevant to the emotion. I am afraid because I believe that the angry man poses a threat to me. In other cases, the tie between the emotion and its object is secured by make-believe, rather than belief. I feel a shiver of horror as I imagine that I have cancer. The belief in question need not be plausible. I fear dying in a plane crash even though I know this is an unlikely event. These observations support a cognitive analysis of the emotions. They make the role of belief (or of make-believe) central in explaining why we respond emotionally and how emotions are individuated. But some other forms of emotional reaction appear to count against the cognitive theory of emotions. Phobias, for instance, are resistant to the correct belief that their object is harmless. I am afraid of feathers, let us suppose, not because I think they might hurt me in some unlikely fashion but despite genuinely believing that they are harmless. The object of an emotion can itself be an emotion. She delights in his suffering. Indeed, one can respond emotionally to one's own emotions. I am embarrassed by my lustful thoughts. The "meta" emotion – the emotional response that takes some other, first-order emotion as its object – often is different from its target emotion, but the two may be the same. I am happy that you are happy. Emotional responses of these kinds all conform to the cognitivist model. One feels the emotion that one does because of holding beliefs relevant to that emotion about its object.

Groups, like individuals, ride emotional roller coasters, sharing everything from jealousy to angst to euphoria. It is vital to know whom you are connected to and possess emotionl awareness in communication with others..

Feelings play a big role in communication. Emotional awareness, or the ability to understand feelings, will help you succeed when communicating with other people. If you are emotionally aware, you will communicate better.

You will find a deeper insight about the importance of emotional awareness in communication and we recommend you to read: https://www.conovercompany.com/the-importance-of-emotional-awareness-in-communication/

Practice Self-Regulation

Self-regulation is a key ability of emotional intelligence. People who can manage their emotions well are able to recover more quickly from stress arousal. This means, at the neural level, quieting the amygdala and other stress circuits, which frees up the capacities of the executive centers. Attention becomes nimble and focused again, the mind flexible, the body relaxed. And a state of relaxed alertness is optimal for performance.

Nonverbal Communication: Reading Bodies, Touching Minds | Teaching Interpersonal Communication in a Business Communication Course

Your Focus Determines Your Mental State

How you manage your emotions is determined by what you focus on.

Think of the mind’s eye as a flashlight. This flashlight can always search for something positive or negative. The secret is being able to control that flashlight—to look for the opportunity and the positive. When you do that, you’re playing to win. You’re able to focus on the right things and maintain that positive self.

And keep in mind that a leader not only has to focus her/his mind’s eye, but helps others focus their minds’ eyes as well.

The focused mind: get your brain to concentrate on what matters

Keeping a focused mind is hard. You sit down, ready to work. You open a new document, and start working on a report that is due tomorrow. Then, your phone lights up. It’s a text from a friend. Do you ignore it and stay focused on the report? Or do you decide to have a quick look at the message?

Every day, thousands of choices like these happen inside your brain. It’s a constant battle between your desire to create great work and your primal need to know what’s going on around you.

While focus can seem like fuzzy concepts, it is actually well-studied when it comes to the neuroscience behind it. And that makes it easier to understand and control. How can you master your attention and concentrate on what really matters so you can achieve your goals faster?

The science of attention

To understand what a focused mind is, you need to understand the concept of attentional field. Your attentional field is the combination of everything inside of you—such as thoughts, emotions, or physical sensations—and everything outside of you—including what you see and what you hear. Focus is the ability to concentrate on cues inside or outside of you in a deliberate way.

When you’re trying to work on something and receive a notification, two parts of the brain are being involved in how you manage your attention. The prefrontal cortex, which is directly behind the forehead, is activated when you start concentrating. The parietal cortex, which is behind the ear, is activated in case of a distracting event.

A long time ago, you would have used your prefrontal cortex when working on a tool or building a shelter. But your parietal cortex would have been instantly activated if you heard a strange noise or if you were attacked by a wild animal. Thus, the parietal cortex is originally a survival tool inside the brain, ensuring that we can switch our attention to more pressing matters if something urgent happens.

Research actually shows that the neurons in these two regions emit pulses of electricity at different rates: slower frequencies for the deliberate and intentional work of the prefrontal region, faster frequencies for the automatic processing of the parietal region.

In today’s world, the sources of distractions are constant, and less likely to be critical to our survival. We get interrupted by a never-ending flow of competing cues and information, and it becomes harder to sustain our attention for longer periods of time. In short, we struggle to stay focused.

Managing the wandering mind

On average, our minds wander almost 50% of the time. Mind wandering is when we think about things that are not going on directly around us, contemplating events that happened in the past, that might happen in the future, or will never happen at all. While intentional mind-wandering can be good for your brain—scientists have foundthat closing your laptop and daydreaming for a few minutes has a positive impact on cognition—studies show that letting your mind wander too often has a negative impact on overall performance in your daily life. Research also shows that too much mind wandering comes with an emotional cost.

Many of the distractors that pull us away from deep work and put our minds in wandering mode are digital, such as emails or text messages. While for most people it’s impossible to completely disconnect when doing work, there are a few research-backed techniques to strengthen your focus so you can achieve more and faster.

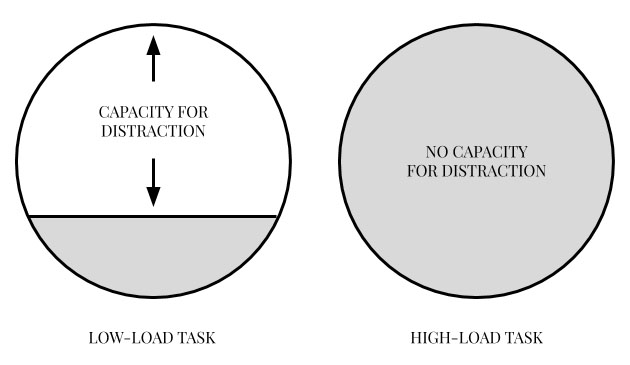

- Manage your distractions: first, put your phone away. And by away, I mean in another room. If you are tempted to check social media on your laptop, install some apps that will prevent you from accessing them for a set amount of time. But managing your distractions can also mean adding deliberate distractions. The Load Theory of Attention posits that because attention is a limited resource, filling all the additional “slots” in your mind may leave no room for other distractions. This is why some people work better when having a bit of background noise or listening to music while in focused mode.

- Monitor your mind: it’s hard to avoid the fact that your mind will end up wandering or that you will get interrupted by external distractions at a point or another. Being mindful of what your brain does is a great way to improve your focus. If you start daydreaming, bring back your focus on the task, and allow yourself to daydream during your next break. This sort of intentional mind-wandering has actually been shown to be good for your productivity and creativity. Other studies show that promising yourself a reward at the end of a task can help you refocus after you got distracted. It’s not about never losing your focus—which would be unrealistic—but about monitoring your attention and using effective strategies to bring it back to the task at hand when you get distracted.

- Strengthen your brain’s circuitry: scientists have designed and tested a technique that acts as a mind’s workout for focused attention. When practiced regularly, this exercise can help make it easier to keep your focus where you want it to be. Simply bring your focus to your breath; notice that your mind has wandered off; disengage from that train of thought and bring your focus back to your breath. It’s the back-and-forth between losing focus and bringing your attention back to your breath that ultimately strengthen the brain’s circuitry involved in concentration.

Try these three techniques next time you want to stay focused on a particular task. Developing a focused mind takes practice, and it’s inevitable that you will get distracted, either by internal thoughts or external events. Building mental strength is all about acknowledging these challenges so you can better manage them. With enough practice, it will become increasingly easier to get in the flow.

Source: https://nesslabs.com/focused-mind

Source: https://www.conovercompany.com/the-importance-of-emotional-awareness-in-communication/